Twenty five. TWENTY FIVE! I find it hard to believe, because it seems like only yesterday that we founded this new society. But if I then think about how much has happened in the intervening time, the truth hits home: our baby not just walks and talks, but runs and is way past adolescence, well into adulthood!

The birth of this new society had a rather long gestation time. I think it was somewhere in 1994 that Hans-Peter Lipp, during a visit to our institute in Paris, remarked that we needed a European society to represent our field in the European neuroscience federation that was being discussed about. The new society would be named “European Behavioural and Neural Genetics Society”. As so often with good ideas, nothing much happened for a while as other, more urgent, preoccupations demanded our attention. But then, in the early summer of 1996, the formation of a European neuroscience federation was gaining momentum. At a reception of the Fyssen Foundation, I bumped into Wolf Singer, then President of the European Neuroscience Association (ENA) and learned that at the forthcoming ENA/EBBS meeting in Strasbourg a gathering of European societies (both national and specialist ones) would be organized to discuss the particulars of the planned new federation. Boldly I told him that we had just founded this exciting new society and would like to be part of the initiative to create a federation of European neuroscience societies. I carefully avoided mentioning the number of members (2) and hope this falls in the category of “little white lies” or, even better, an optimistic exaggeration. Singer told me to write a letter so that our new society could be invited to the meeting. Time was short, so we had to get moving.

I tried to contact Hans-Peter to tell him about this, but he was at his research station in Russia and could not be reached. But as soon as he came back, we contacted some colleagues and formed a provisional executive committee. Next, I wrote a letter to the ENA (see image) and announced the formation of the new society and our commitment to the European neuroscience initiative. Again, I carefully avoided mentioning how many members we had (by then we had tripled in size to 5 or 6), only listing some countries where our friends were located. The letter is dated July 15, 1996, which, I think, can be regarded as the birth date of EBANGS. From there, things went fast. Hans-Peter set up a website (something many existing societies did not yet have at that time) and we started recruiting members. As we had no expenses for the moment (the website was hosted on Hans-Peter’s institutional server), we did not charge a membership fee (and at the same time saved ourselves a lot of work) and membership boomed. As hoped for, we received an invitation for EBANGS to participate in the meeting in Strasbourg, where I was present representing the newly founded society.

First official letter from EBANGS to ENA, dated July 15, 1996

Shortly thereafter, the Behavioral Neurogenetics Initiative, a small group of mainly French and US researchers financed by the French Embassy in Washington, organized a summer school and a symposium in Orleans, where our Paris institute had moved to in early 1997. We decided that, with together more than 100 participants already present for these events, this was a great opportunity to organize the first meeting of the fledgling society. About 50 people did indeed stay on for the first EBANGS meeting.

At the business meeting, the provisional executive committee was formalized. In addition, several US colleagues were present who remarked that they’d like to join this new society, given that it was the only one explicitly combining behavioral and neural genetics. Of course, the more the merrier and nobody objected to non-Europeans joining EBANGS. If my memory is to be trusted, it was the late F. Robert Brush who suggested to change the society’s name from “European” to “International”. Bob proposed to maintain the British spelling of the name, as a reminder of our European roots. This proposal was accepted and IBANGS was born. The new name raised some worries from the side of our European sister societies. At the meeting in Berlin in 1998 where the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies was founded, the issue of us not being purely European anymore was raised. However, I assured our colleagues that IBANGS was firmly committed to FENS and half an hour later I signed the founding document of FENS on behalf of IBANGS. More than 20 years later, IBANGS is still a member of FENS, helping to determine the course of European neuroscience.

FENS Council, minutes after the founding document was signed. Representing IBANGS, I stand second from left.

Also at that Berlin meeting, I had several discussions with publishers that were interested in starting a new journal for IBANGS, which after almost two years of negotiations resulted in the creation of Genes, Brain and Behavior, published by the Danish publisher Munksgaard, a full daughter of Blackwell (now Wiley-Blackwell). Baby IBANGS was coming of age!

By now, 25 years later, we can look back on a series of wonderful annual meetings, a strong, dedicated membership, and an illustrious list of Distinguished Investigator and Early Career awardees. Since the founding, numerous people have contributed to the success of the society in leadership positions, from presidents to committee members. We are indebted to them for their dedication. For many years now, thanks to the hard work of John Crabbe and Mark Rutledge-Gorman, the society has received funding from NIH, enabling us to award travel grants to students, postdocs, and early career faculty to attend our meetings. IBANGS has become a mature, vibrant society serving an active community and I for one can’t wait to see what more the future will bring us!

Note: edited Nov 11, 2020 to clarify sequence of events after checking my archive, streamlined, and added a photo.

The reason I came to read such an old and relatively obscure book was that while inserting some recently-acquired books into my collection, I stumbled upon it and realized that I didn’t remember ever having read it. My copy is in

The reason I came to read such an old and relatively obscure book was that while inserting some recently-acquired books into my collection, I stumbled upon it and realized that I didn’t remember ever having read it. My copy is in

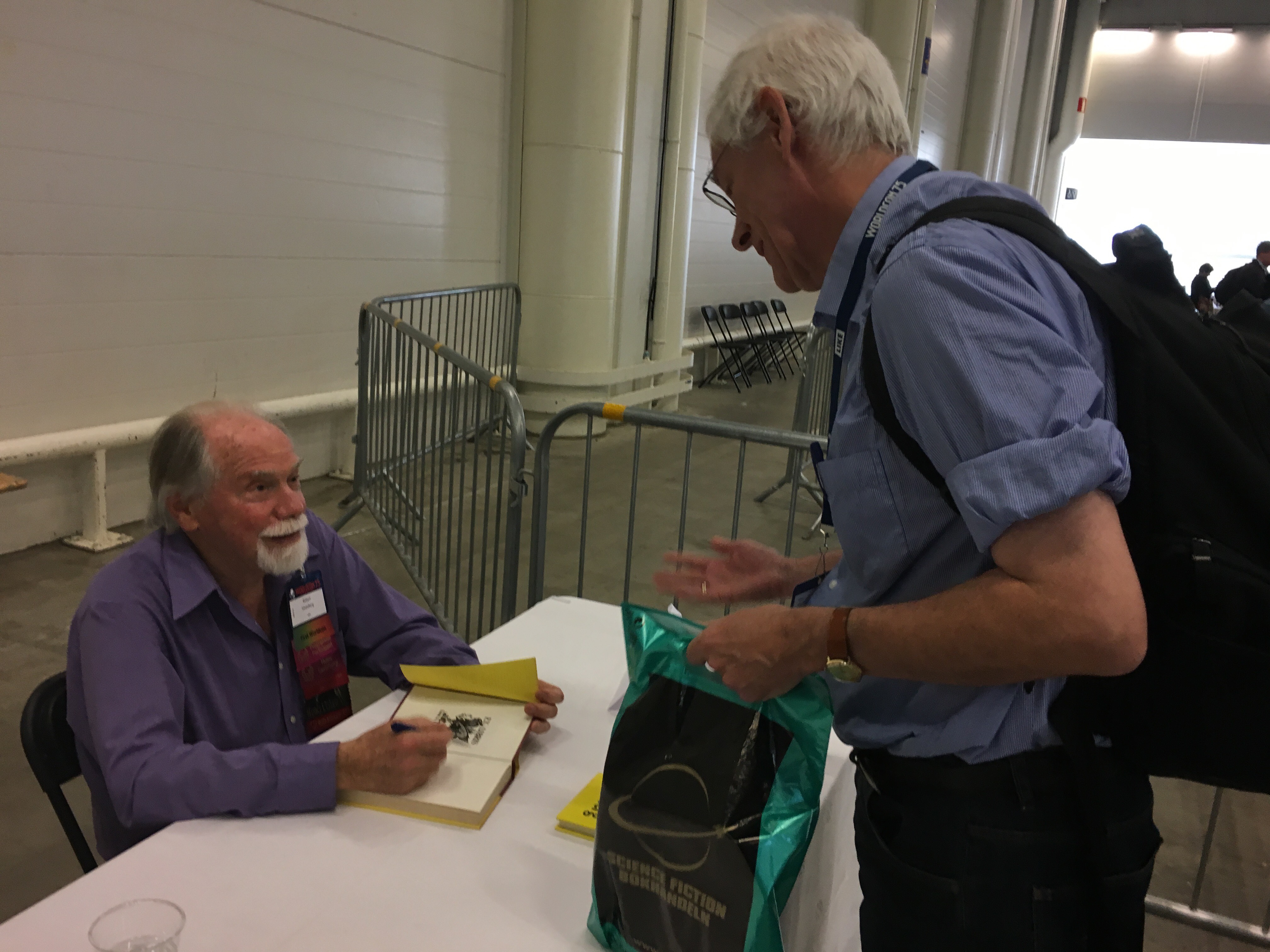

Although I had seen his name before (mainly on Amazon reading recommendations), I had never read anything from this author before. I liked his presence at the meeting and found his remarks insightful and funny, so I decided to buy one of his books, which he graciously signed for me.

Although I had seen his name before (mainly on Amazon reading recommendations), I had never read anything from this author before. I liked his presence at the meeting and found his remarks insightful and funny, so I decided to buy one of his books, which he graciously signed for me.

notice on the first page, I had acquired it in 1978 and presumably I read it around that time. Most likely that was the second time that I read it, as I had by then devoured every SF book that our local library had to offer. In any case, I had only a faint recollection of the book: it involved a lot of beach and human relationships that included sex (I had a definite recollection of somebody saying “

notice on the first page, I had acquired it in 1978 and presumably I read it around that time. Most likely that was the second time that I read it, as I had by then devoured every SF book that our local library had to offer. In any case, I had only a faint recollection of the book: it involved a lot of beach and human relationships that included sex (I had a definite recollection of somebody saying “